Gold Plated

As part of the Monetary Control regulations put in place by the Federal Government during the war, CBA – as the country’s Central Bank – was authorised to handle the country’s gold reserves. This meant that anyone in possession of gold had to deliver it to the Commonwealth Bank in return for a payment at a price fixed by the bank. This extended to gold processing with the Perth and Melbourne Mints (along with two other companies) both appointed as agents of the bank. The war years saw 7.1 million ounces of gold processed under this arrangement, the bulk of which was sent to America every four weeks to pay for war supplies.

Gold Dust

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour in December 1941, bringing the USA into the war, the shipping of gold overseas became more precarious so an arrangement was made with the Bank of England for the gold to be purchased and then stored in Australia until shipment became safer. As the Japanese pushed south towards Australia, the decision was made to move the country’s gold inland. The selected site was the Broken Hill jail, and in April 1942 - amid great secrecy - a special train manned by select CBA staff made the journey west. Bank officers guarded the gold for three years when it was returned to Sydney in April 1945. This was the largest movement of gold in Australian history.

Gold Coast

The shipping of gold was a dangerous exercise as underlined by the loss of the Niagara, which sank in June 1940 while transporting one of the bank’s consignments to the US. The Niagara went down in 428 feet of water in the middle of a minefield in Whangarei Harbour on the east coast of New Zealand’s North Island. The gold was worth a huge amount of money - 2.5 million pounds (140 million pounds, $255 million today) – so a salvage operation was amounted to recover the cargo. The exercise took 15 months to complete and the team salvaged 94 per cent of the gold in one of the most successful operations at the time.

Telling Times

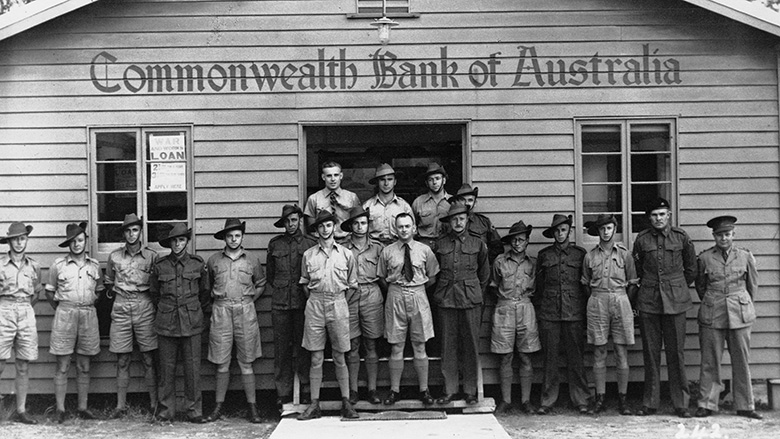

Just as it had in WW1, CBA played a critical part in ensuring the country’s service people got paid. As part of its policy to take the bank to the people, agencies were established in military camps and operated by bank staff after their branches closed for the day with banking services provided at night. As the war went on, these services were taken over by the Post Office. But in bigger camps special branches of the CBA were opened. The bank also handled payment and transaction services for the US Forces of whom two and a half million service people passed through Brisbane alone during the war.

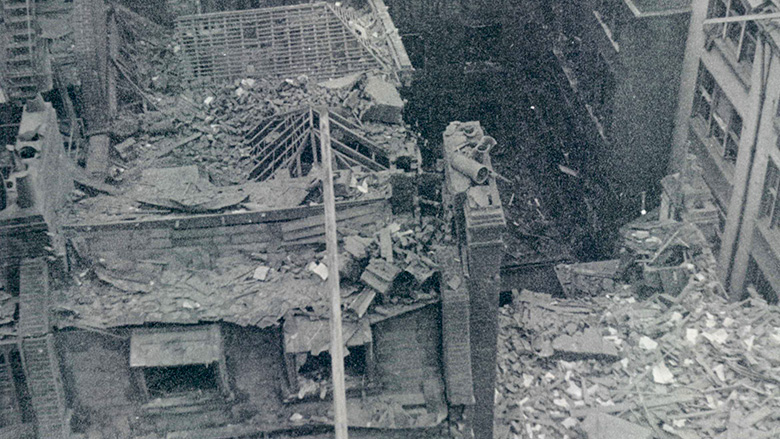

CBA's London Branch bombing aftermath (Reserve Bank of Australia Archives; PN-004234)