From her pristine and well-equipped clinic in the Commonwealth Bank’s renowned “Moneybox” headquarters in Pitt Street, Sydney, Sister Elizabeth Murrell had more than a passing interest in the outside world that she could view from her gleaming windows in April 1920

Having survived the horrors of World War One as one of 3,000 Australian nurses who had cared for wounded, sick and dying Allied soldiers on battlefields from the Middle East to the Western Front, the 40 year-old medical professional was well-acquainted with the risks posed by disease and infection - no matter how young or healthy her patients might appear to be.

She had also seen more than her fair share of death caused not by a bullet or shell wound but by dysentery, malaria and black water fever during freezing winters and mosquito-ridden summers in the makeshift field hospitals of Salonika in Greece where she had been posted in 1917.

It was this knowledge that had drawn her to the Commonwealth Bank on her return from war in November 1918 – a return born of personal and painful experience after her discharge from military service that same year on the grounds of being medically unfit.

Like the many soldiers she had cared for, Sister Murrell had fallen victim to the very debilitating illnesses she had sought to treat.

After recovering from her sickness, she had resumed her nursing career at Randwick (now the Prince of Wales) hospital in Sydney when the call came to join the CBA in 1919. The letter was from none other than the Bank’s Founding Governor Denison Miller (who today we would know as the chief executive and managing director).

In April 1919, the world and Australia was in the grip of another global war. While the guns on the western front had fallen silent the previous November after four years of devastating conflict, another, even more brutal killer was stalking nations across the globe.

Even countries which had been mercifully left untouched by warfare were now falling victim to a virus which was indiscriminate about who it touched, infected and, in far too many cases, killed.

If WW1 had shocked the modern world with its estimated 20 million dead, the Spanish flu pandemic between January 1918 and December 1920 left it reeling. Of the 500 million people thought to have been infected – equal to a quarter of the world’s population at the time – a staggering 50 million are estimated to have died.

Denison Miller had, like Sister Murrell, seen the devastation left in the wake of war and pandemic at first hand. While hundreds of thousands of Australian servicemen had travelled overseas during WW1, Miller was one of the few privileged civilians to make an international trip in the last months of the war to witness for himself its impact on North America, Britain and Europe.

What his tour hadn’t quite prepared him for was the ravages being caused by the Spanish Flu. No country was immune, no people unaffected.

Writing afterwards of his experience, the Governor told CBA’s staff: “Windows in all the tram cars were taken out and all the attendants in the shops and large offices wore masks while in some of the states coming across Canada we had to wear our masks in the train.”

That episode was repeated in London and Auckland on his way home and in uncanny parallels with the pandemic 100 years later, Miller was on-board a ship, the Makura, which was carrying a number of passengers with suspected influenza cases.

Like today, Australia had introduced strict border and immigration controls under the 1908 Quarantine Act to prevent the transmission of Spanish Flu. The Makura was sent to Sydney’s Quarantine Station on Manly’s North Head where Miller and his fellow passengers spent a minimum of seven days.

Luckily for the governor, no further cases were detected and he and his colleagues were released from Quarantine on 21 December 1918.

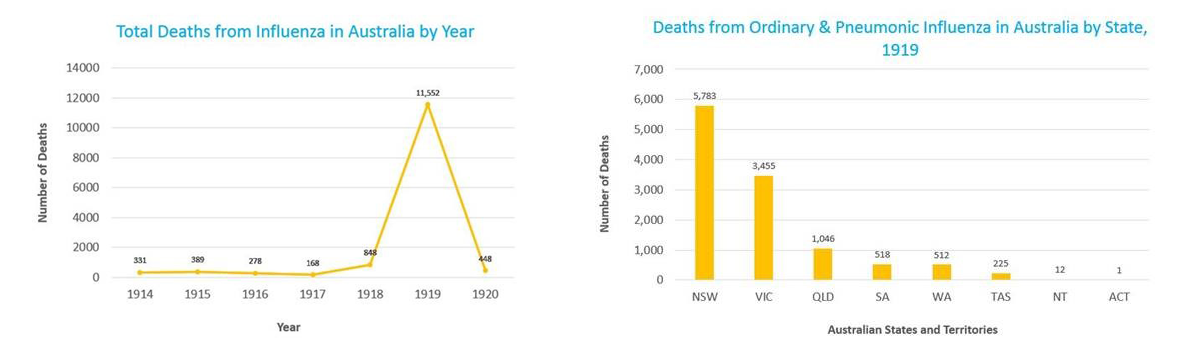

The Governor re-emerged into a country that was struggling to cope with the growing threat posed by the pandemic. At the end of 1918, 848 Australians had died from the Flu. Over the next 12 months that number soared to 11,552.

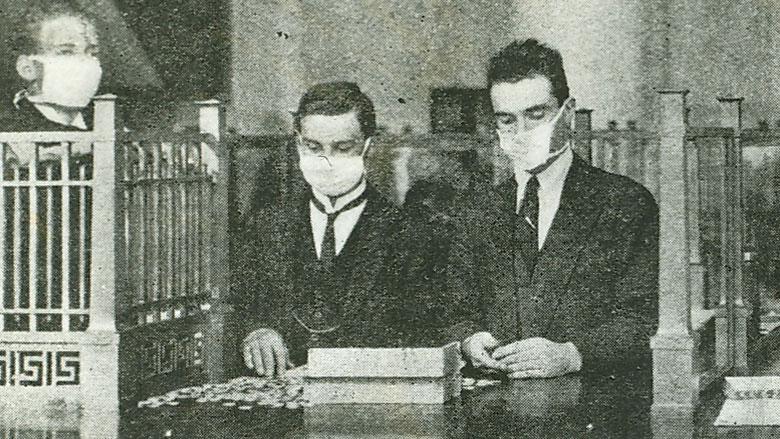

Miller knew that the bank had to take steps to protect both its staff and its customers. American newspaper reports in 1918 had attributed the spread of the disease to germs being transferred via dirty bank notes. While this was later proved incorrect, at the time it was considered a real possibility.

The Bank quickly took a role in educating the public about the benefits of keeping bank notes clean and made bank wallets available in branches in an attempt to prevent the virus’ spread.

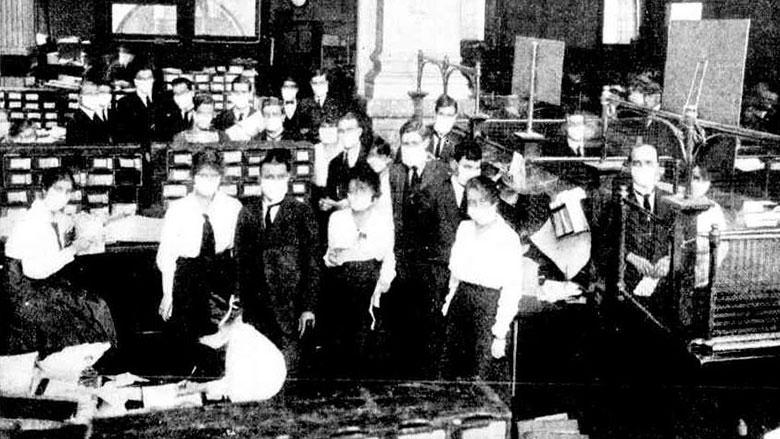

In January 1919, the Governor instituted the wearing of masks for all staff in Sydney. Shortly afterwards, images of staff wearing masks appeared in local newspapers.

According to the staff magazine Bank Notes, government institutions and large firms followed CBA’s lead and implemented the wearing of masks in the work place. By February, the government announced that the use of masks in public was mandatory. Those that did not comply could incur fines or imprisonment.

Despite the precautions, the strain on staff became evident at the Bank’s Head Office in Martin Place. That’s when Miller turned to Sister Murrell, appointing her as CBA’s first medical officer, with the job of caring for the staff if they got sick and introducing measures to prevent the spread of the flu.

Among these were a decision to close the office each day at noon from the 22nd April, the result of reduced staffing levels and increased stress levels amongst those did make it into work.

One of the aims was to provide staff with time to rest although where necessary some members would remain until 3pm to meet banking requirements. Early closure also became a reality for branches where staff were heavily affected by the disease.

These rules mirrored government-initiated restrictions as traffic between states was stopped temporarily, some schools were closed early and public gatherings were minimised to avoid the further spread of the virus.

But 1919 was a hard year to bear as increasing numbers of war-battered soldiers came home to a grateful people, only to find themselves dealing with another tragic set of circumstances and military-style orders designed to keep them apart from their loved ones and their communities.

As the two most populous and therefore most at risk states, NSW and Victoria bore the brunt of the infections and related deaths. Just as they are doing 100 years on.

Slowly but surely, however, the transmission of the pandemic was contained. As the New Year – and a new decade – progressed both transmission and death rates started to fall. By the middle of 1920, the peak had been reached and the curve of both, as we know of them today, had been flattened.

By the mid-to-late spring the number of deaths had fallen to almost the same level as to when the pandemic had started to make its deathly presence known just over two years before. Year 1920 ended with 448 deaths, taking the overall toll across Australia to 15,000. The greatest killer of recent modern times had exhausted itself.

For Governor Miller and Sister Murrell there was quiet satisfaction that the pandemic had claimed just four lives amongst CBA’s staff. While that may have been four too many, they could set that against the 26 of the Bank’s young men who went off to war between 1914 and 1918 and never returned.

Never ones to highlight their own efforts to contain the devastating effects of the pandemic, it was left to others to comment on the contributions of quiet achievers such as Sister Murrell.

In an article for CBA’s then staff magazine Bank Notes in November 1919, an unnamed writer who was being treated in the Chief Medical Officer’s Pitt Street clinic, noted: “In two rooms full of sunshine glistening white with the gleam of polished nickel and plate glass, conveying the hospital touch, Sister Murrell sits, white coiffed and white gowned, alert and ready to squelch the many maladies that beset the path of the toiling bank clerk.

“Sister says she finds us as ‘cases’ a very healthy, uninteresting lot from a professional standpoint and rightly so, she says. With the splendid building we are in and the healthy conditions generally, how could it be otherwise?

“And then Sister gets a reminiscent look in her eyes, the shadow of a sigh escapes her as she remembers the fine lives ‘gone west’ and from a sentence or two, you learn that men in hospital huts in frozen Salonika did not exactly live in the lap of luxury.”

Little more than a year after those words were written, Elizabeth Murrell was able to turn her hands to the mundane task of caring for Head Office staff with more minor ailments as the pandemic faded away.

Honoured by Governor Miller in January 1920 for her war service, she became an institution at the bank, introducing new innovations such as midday exercise sessions for female staff, health talks and after-hours physical culture classes. She also helped to establish the bank’s hospital cot committee, part of the staff club that supported local communities.

Known as “Beth”, Sister Murrell stayed with the bank until retiring in June 1937. Her thank you presents at a farewell tea party held at the Pickwick Club in the Sydney CBD included a handbag from the staff and a wallet of notes from the bank’s deputy governor. She spent her retirement in Dee Why on Sydney’s Northern Beaches, passing away in November 1970, aged 90.

As for Denison Miller, the founding father of the “bank for all Australians” he was knighted by the Prince of Wales in 1920 on behalf of a grateful British Empire for the role he had played in helping the fledging Commonwealth of Australia get through WW1 and supporting the efforts to rebuild the nation in the face of the pandemic and the resulting post-war economic slump.

A man of great principle whose calm and stoic approach, it was said, was appreciated by all those who came in contact with him, Miller died suddenly of a heart attack three years later. He was 63.

On his death, the distinguished Australian writer Edward Vance Palmer said that while the Governor’s personality was “neither dramatic nor colourful it made a deep impression on the public mind”. The new bank, he wrote, might have been as outstanding a failure in the hands of the wrong man, as it had been a success in Miller's. His ability to secure co-operation and loyalty was not the least of his strengths.

Palmer may well have been describing the very essence of the institution Miller left behind – a bank literally forged in the heat of a global war and the furnace of the pandemic that followed. A hundred years later those very strengths have again come to the fore as history once more seemingly repeats itself.

By Commonwealth Bank’s Editor-in-Chief Danny John, and the Information and Archive Analyst Juli Liddicoat