Commonwealth Bank is commemorating the centenary of the Armistice with a collection of podcasts, articles and videos remembering those involved in World War One.

The economic effects of the war were felt far and wide across Australian business and commerce and, by extension, the everyday lives of the country’s five million people.

Not only did the conflict and the peace that followed need financing in a massive way, management of the national economy underwent radical change. Just as the Bank had taken the lead role in raising the money to fund the war, it also found itself at the centre of that transformation.

Disruption to international trade

The war dramatically disrupted international trade and the pre-1914 system of payments that supported it.

Use of the long-standing gold standard and its administration by the City of London, whereby payments were linked to the price of - and guaranteed by - a country’s holdings of gold – was effectively abandoned. It would be many decades before a replacement system – based on a floating price of major economy reserve currencies - could be established.

Gold still had a key role to play, however, especially in the early years of the war with its importance not lost on the Australian government, which prohibited the public export of the precious metal. With hard currency in short supply and a need to pay for munitions, among other things, the Bank was called upon to organise a number of urgent and secret shipments on the Government’s behalf.

Australian exports vulnerable

Preparation and packing of the gold was often carried out after banking hours, with the shipments undertaken at night.

On one such occasion, one million sovereigns - which today would each cost $945 to buy - were carried down the Swan River in Western Australia in small boats by Bank staff under naval escort and then transferred to a bigger ship at sea to be delivered to their eventual destination. Shipments were sometimes suspended or abandoned because of enemy naval threats.

As exciting and dangerous as that example appeared, it also underlined the difficulties that lay ahead. As a new nation on the map, and one requiring money to build its global trading position and finance its domestic needs, Australia was extremely vulnerable to the unprecedented changes underway.

In particular, its reliance on primary products such as wheat, meat, wool and dairy goods to earn export income increasingly exposed it to the war-ravaged vagaries of the world’s fragmented trade and financial systems.

This greatly undermined the individual and separate elements of Australia’s day-to-day trading sectors, such as wool brokers, grain merchants and meat buyers.

Additional problems were caused by an immediate and significant reduction in the number of available merchant ships for the export and import of goods, as did a fluctuation in demand for Australian products in its major overseas market, Britain.

Miller takes charge

A new centralised system of management and financing was required to run and control these different competing, but also interlinked, needs and the Bank and Governor Denison Miller were best placed to do this.

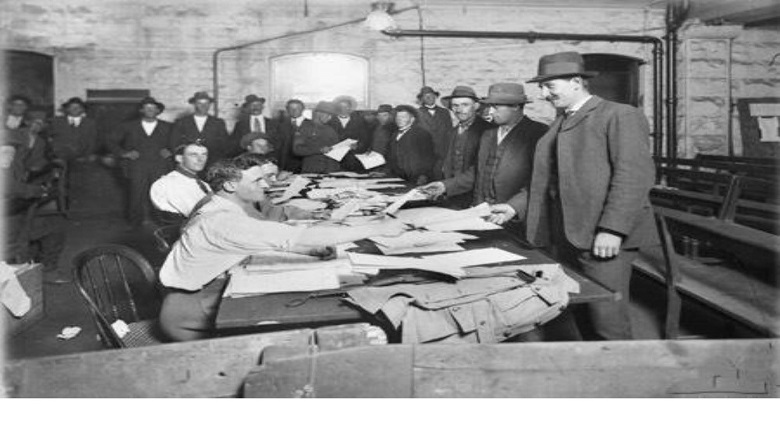

Commodities were pooled, allowing for exports to be controlled on a priority basis, which saw CBA provide the lead finance, supported by the other private trading banks, to literally oil the wheels of trade.

Wheat had been the first commodity covered by the new arrangements through the creation of the Australian Wheat Board in 1915. All of the country’s crop was bought by the government and stored in central depots in each state. The private banks negotiated their share of the financing on a pro-rata basis according to the deposits they held in the state concerned.

In the first pool, CBA accepted any part of the business not taken up by the trading banks. But by the second one in 1916-17, the Bank took control of all the financial arrangements, including organising the quotas of the other banks, making adjustments between them and distributing the payments to corresponding banks in London that were responsible for funding the other end of the trade.

The wool clip was another prime example of the Bank’s involvement in the commodity pools. Demand for wool to produce uniforms meant the British Government acquired the whole of Australia’s production between 1916 and 1920. Again, CBA took responsibility for the entire financial arrangements of the trade.

Australian-style solution to ship shortage

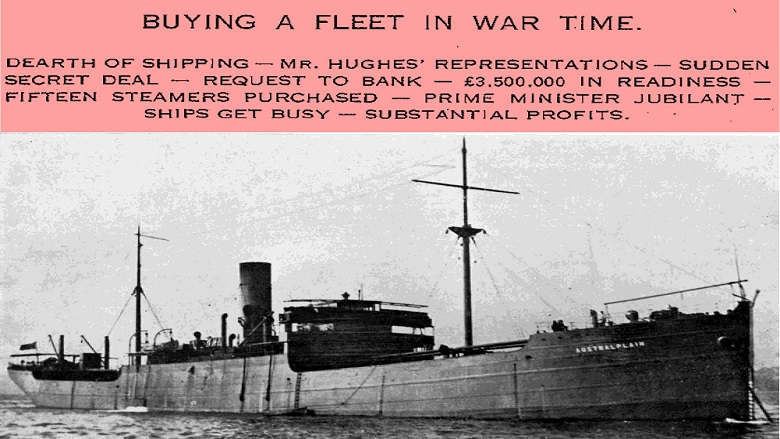

But such movement of goods and produce needed ships and Australia was desperately short of them. Requests for help to the British Government from Prime Minister “Billy” Hughes, who had replaced Andrew Fisher in 1915, came to no avail, but in doing so, gave rise to a truly novel and “innovative” Australian-style solution.

As he headed to London in 1916, Prime Minister Hughes agreed with Miller for £3.5 million to be held on account at the Bank’s offices in the City. Without the knowledge of the British Government or the major shipping lines, Hughes arranged for a ship broking firm to secretly buy up to 30 vessels on Australia’s behalf.

From London, he dashed off to France, but just before his train left Victoria station, Hughes thrust a bundle of papers into the hands of the Bank’s London branch manager, Charles Campion, and told him to go ahead with the purchase while he was away.

Campion managed to acquire 15 cargo steamers at a total cost of £2,052,654, which was to form the basis of the publicly owned Commonwealth Shipping Line.

The British authorities were somewhat displeased at the move, but allowed Hughes to go ahead with the deal as long as he promised not to buy any further vessels. The fleet was subsequently augmented by German and Austrian ships seized by the Australian government from their owners.

Laying foundations

Those episodes of macro-economic management underlined how significant the Bank’s role had become in the nation’s affairs by the end of the war.

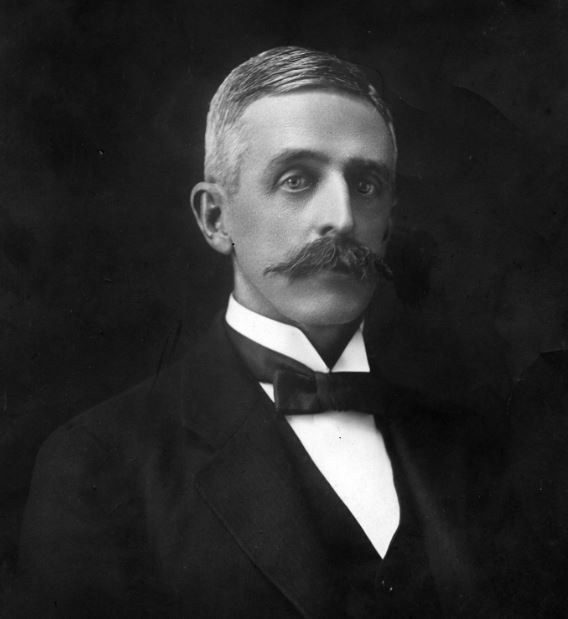

Bank Governor Denison Miller

From a new and tiny institution, compared with the finances and operations of the private banks, CBA had quickly become an integral part of the banking system. This was thanks largely to the central powers of the equally new Federal Government - interventionist powers that had to be employed if the country was to fight an effective campaign on the battlefield and the home front.

This was not lost on Miller, whose plan from the beginning had been to lay the foundations for the Bank to develop into a true central bank that sat at the centre of the economy.

This was to continue in the years after the war with the Bank’s on-going involvement in the producer pools, paying and helping to repatriate returning soldiers and providing the finance and assisting with the construction of homes for them.

CBA became the national agent for the Commissioner appointed under the War Service Homes Act of 1918 to provide land and homes for service people. Under that arrangement the Bank built 1,777 houses at a cost of £1,555,119 and acquired a further 5,179 for £2,874,502.

In 1920 the Bank and Miller’s contributions to the country in war and peace were recognised with a knighthood for the Governor.

Such was the influence of CBA’s leader that the Sydney Morning Herald was to comment later: “Sir Denison Miller played a part the value of which cannot be assessed in monetary terms.

“He was in finance the Government’s chief of staff, director of strategy, intelligence and publicity bureau. Every Administration, whatever its political doctrine, acknowledges its debt to this just and provident steward.”

Jaqui Lane is the author of a forthcoming Official History of Commonwealth Bank of Australia, due to be published in 2019.

Sources of information, images: Reserve Bank of Australia Museum; the Australian War Memorial; CBA Archives; Obituaries Australia; The Bankers Magazine (London), 1918; CommBank History pages; Lane, J., Official History of CBA:, the Perth Mint; Faulkner, C., The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (John Sands 1923).